Books by John Janovy, Jr.

Collections of Essays on Natural History,

Philosophy, and the Environment, as well as fiction

All copyrighted by John Janovy, Jr.

KEITH COUNTY JOURNAL

Keith County Journal was originally

published in 1978 by St. Martin's Press, and has been re-issued in paperback by

the University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, NE 68588-0484. KCJ received

excellent publicity in the national media, subsequently sold well, and was, of

course, a very hard act to follow. An excerpt:

I have had only one right brush, and the tip no longer points. It was in

my father's desk, and we found it after he died. There is no way to know how old

it is, or what brand. It is simply black with a brass sleeve to hold the hairs,

which are lighter than those of many brushes. I knew the first time it was a

right brush. The picture turned out to be so much better than my perceptions of

my own ability would allow.

BACK IN KEITH COUNTRY

Back in Keith County was originally

published in 1981 by St. Martin's Press, and has been re-issued twice in

paperback by the University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, NE 68588-0484. The theme

is intellectual freedom, a subject that was very much on my mind after several

years of foreign travel. An excerpt:

Harry Heron came into camp in a box. The first thing he tried to do was

get cold and die. The second thing he tried to do was stab Jim's left eye out.

He fell a little short of success in both cases. . . He smelled pretty bad, too,

and it got worse. In fact, the more I try to remember what Harry was like, the

grubbier he becomes. I will say this for him: he finally did become paper

trained. He accomplished that when people moved him over to where the papers

were and kept him there. All things considered, he was the filthiest, dumbest,

ugliest, most bedraggled, hopeless case ever to arrive. . . Well, with all those

things going for him, you couldn't help falling head over heels for Harry

Heron.

YELLOWLEGS

YELLOWLEGS was originally published in 1980 by St.

Martin's Press, and later issued in trade paperback by Houghton-Mifflin. It has now been issued as an e-book by MacMillan and is available on all e-readers. The

unsolicited letters indicate people either hate it or consider it a cult piece.

An excerpt:

Pops looked for a long time at the feather, the man off the highway, then

back again at the feather. He finally took it gently, holding it in the light

for a moment, turning it over and over, holding it back in the shaft of light,

holding it over under the bulb by the cash register, flattening it against his

palm, holding it up to the window to look through, and at last smiling.

"That's a yellowshanks feather," he said, "come off up by the wing."

ON BECOMING A BIOLOGIST

Originally published by Harper and Row in 1985,

On Becoming has now been re-issued in paperback by the University of

Nebraska Press, Lincoln, NE 68588-0484. An excerpt:

I am reminded . . . of some decidedly simple yet brutally honest and

practical advice I received at the start of my doctoral work. I was on a tour

through the National Institutes of Health in the tow of my mentor, Dr. J. Teague

Self. I had at that point been Teague Self's graduate student for about two

weeks. Walking down the hall, he cocked an ear at a blustery Irish voice

emanating from an office, poked his head inside, then turned back to me and said

"How'd you like to meet Coatney?" [G. Robert Coatney, in his office with A.

M. Fallis and J. F. A. Sprent.]

I can think of no time since in which I've seen any other student so suddenly

flung alone into a room full of his heros. . . . Coatney issued the advice which

put all idealism into perspective, the hindsight of a long and successful

career, and which spoke of a hazard never imagined by the young.

"Always," said G. Robert Coatney, "be finishing something."

FIELDS OF FRIENDLY STRIFE

Strife is subtitled The Relationship of a Father, Daughter, and Sport. The book is my statement about teaching

and learning, especially the teaching of oneself through the seeking of

challenges and the learning that accompanies such exploration. The book was

first published in 1987 by Viking and subsequently issued as a Penguin

paperback. An excerpt:

The fear of failure keeps so many thoughts inside a head, so many men and

women in their chairs, silent, acceding, not wanting to be thought a fool, or

stand out, or gather social species' hate for doing well, or poorly, or any

other way but average. How much raw intelligence, ability, vision, lies fallow

in such fear? A world and then a world, is how much. Such a load to place on

ball. But . . . what's lost is gone, no matter what it is. If you want them

badly enough to drain your mind and soul in front of screaming mobs and pounding

drums, the points become all things lost through the ages: Pride, love, hope,

and most importantly, the fear of failure itself.

VERMILION SEA: A NATURALIST'S JOURNEY IN BAJA CALIFORNIA

Vermilion Sea (Houghton Mifflin, 1992). subtitled A Naturalist's Journey in Baja California, was written

after several unsuccessful attempts at fiction, and is actually an admission

that essays on natural history, and the intellectual domain one can construct

around natural settings, were my stock-in-trade. The setting is Baja California;

the theme is that of pure exploration in a charmed universe--a metaphor for our

earliest attempts at research. Vermilion Sea is now available as aKindle e-book and also on all other e-readers via Draft2Digital. An excerpt:

I get the sense, from reading Pablo Martinez, that regular psychic

interactions with landscapes such as that north of Cataviña had a way of

building a shield between humans and the forces that sought to domesticate them.

In my experience such sacred places still function in that manner. Natural

scenery associated with difficult, but deeply satisfying, intellectual endeavor

reminds me of the positive feelings that come with tangible accomplishments,

with personal discoveries.

DUNWOODY POND: THE HIGH PLAINS WETLANDS AND THE CULTIVATION OF NATURALISTS

Dunwoody Pond, subtitled Reflectionson the High Plains Wetlands and the Cultivation of Naturalists, is an homage to my students, and it

consists mainly of the stories of graduate students' struggles

with their research problems. The book was published in 1994 by St. Martin's

Press and has been re-issued as a Bison Books paperback by the University of Nebraska Press. There really is a Dunwoody, a Dunwoody Pond, and a species of parasite

[Steganorhynchus dunwoodyi] named after the person and place. (I

encourage my students to name their new species in honor of the land owners who

give us permission to use their property.) An excerpt:

But the people who've walked into my laboratory are rational beings who

have enormous faith in their own very human talents, and little use for

prophets. They attack gigantic problems with only their minds and hands. They

are models for a type of human being that takes pride in its brain, in its

ideas, instead of in its weapons or power. So I've set about to tell their

stories. We need to know where these kinds of people come from, how they are

shaped, and how they think, with the hope that in the telling, we'll discover

how to generate some more of them.

TEN MINUTE ECOLOGIST: TWENTY ANSWERED QUESTIONS FOR BUSY PEOPLE FACING ENVIRONMENTAL ISSUES

Ten Minute Ecologist (St. Martin's Press, 1997) is subtitled Twenty

answered questions for busy people facing environmental issues. Each

question is answered with a short, 5 or 6 page answer; chapter titles range from

"How do humans view the world?" to "Why study islands?" and "Why do scientists

argue?" The book includes a glossary, as well as a long list of suggested

readings for those who want to explore ecological issues more thoroughly. TME has been translated into Italian and Japanese. A second edition is now available as a paperback, ideal for students, and as an e-book on Kindle and all other readers via Draft2Digital. An excerpt:

The third important property of dirt is its organic content, that is,

living organisms and their products . . . A partial list of soil dwellers

includes: bacteria, algae, fungi and their spores, amoebas, nematodes,

earthworms, tardigrades, rotifers, mites, insects, rodents, tapeworm eggs, roots

of surface vegetation, pollen, and seeds. . . A brief list of organic products

includes bark, leaf pieces, cell wall pieces, egg shells, hair, and dead bodies.

A common organic component of soil is feces. All animals, no matter how large or

small, defecate regularly, and the overwhelming bulk of their feces ends up in

dirt. In fact, insect and worm feces are among the most frequently encountered

components of our environments.

Strange as it seems, some people like to eat dirt.

TEACHING IN EDEN: THE CEDAR POINT LESSONS

Teaching in Eden, (Routledge Falmer, 2003) subtitled The Cedar Point Lessons, is my attempt to explain the success of the Field Parasitology course at Cedar Point Biological Station. The book is fairly serious pedagogy and in some places teaching theory. It also addresses, however, the Arts and Sciences ideal, and particularly the integration of the two. An excerpt:

What would I do if I were a professor of English instead of invertebrate zoology? Where is that intellectual paradise for a teacher of modern fiction? Of poetry? And once I find it, how do I take its pedagogical power and give that power to my students. I'm going to step beyond my bounds and try to answer those questions, then step even further beyond those bounds and try to answer them for history, economics, engineering, music, and art. I believe that along with literature and science, these five fields encompass all of the basic domains of reality found in human scholarly endeavor. I don't have a professional's, or a professor's, knowledge of these seven disciplines. But if, with respect to these seven areas of intellectual pursuits, we ask the following questions: What is a fact? What is an observation? What evidence do we need in order to make a decision? How do we interpret information? What use do humans make of our products? And what is the fundamental nature of [our] prevailing paradigms? Then the answers will tell us most of what we need to know to build Eden.

FOUNDATIONS OF PARASITOLOGY, 9th Edition

Larry Roberts is the senior

author of the 5th, 6th, 7th, 8th, and 9th editions of Schmidt and Roberts' Foundations of

Parasitology; Larry asked me to be a co-author of the 5th and subsequence editions following Jerry Schmidt's

death. It was a great honor to be a part of this book project. For me,

FOP5 was also a crash course in areas of parasitology long forgotten and

ignored. The cover shown here is from the 9th edition. Steve Nadler was added as a co-author for the 9th edition. This book is now available as a free download on the American Society of Parasitologists web site. An excerpt:

Echinostoma trivolvus is distinguished by a rather remarkable list of

definitive hosts, including several species of ducks, geese, hawks, owls, doves,

flamingos, dogs, cats, guinea pigs, rabbits, pigs, rats, and of course mice. . .

For anyone who thinks all the world's systematic problems are solved or easily

solvable, a journey through these discussions in the echinostome literature

would be exceedingly educational.

OUTWITTING COLLEGE PROFESSORS: AN INSIDER'S GUIDE TO SECRETS OF THE SYSTEM

Outwitting College Professors is subtitled A Practical Guide to Secrets of the System. The book is intended to be somewhat subversive, but at the same time a true set of advice on how to maximize the value of your college education. You're paying a bundle for that college experience, so you might as well get all, not just some, of the long term benefits. That's what this book is all about. A sixth edition is available now on Kindle, and a nice paperback (gift!) and on all other e-readers via Draft2Digital An excerpt:

The second piece of advice for males is to make sure you can speak the English language with simple grammatical rules in place. I don't know why males tend to use incorrect grammar more than females, and maybe my 40 years of college teaching and 20,000 grades awarded don't represent a good sample. But I can assure you that one of the quickest ways to create a bad impression on any teacher is to say "I've went . . ." or use the non-word "alot" in a written assignment. A chapter on dress may not seem like the best place to talk about grammar, but clothes and speech go together, and a male student who comes in to a faculty office wearing his cap on backwards and saying "I've went . . ." might as well be writing C or D on his grade sheet right now.

THE GINKGO: AN INTELLECTUAL AND VISIONARY COMING-OF-AGE

The Ginkgo is subtitled An Intellectual and Visionary Coming-of-Age because that's exactly what it is, not only for the main character, but also for the nation. The Ginkgo is a tale built around the subtle conflict between two cultures. The main character is a student who’s come to a large university from an isolated ranch on the American high plains. The student symbolizes a truly creative mind learnin g how to realize its full potential; her former high school classmates represent society’s pre-occupation with a traditional culture that may not be exactly what it seems. We participate main character's life by reading what she’s written about her past experiences, her thoughts, feelings, desires, and observations. We participate in the traditional culture through a variety of literary devices, but primarily that of a teacher who recognizes this student’s creative potential and is determined to make it a powerful weapon for changing society. The main character chooses a ginkgo tree as her means of exploring her new environment (the university), and eventually envisions her traditional culture a thousand years hence, when her chosen ginkgo tree dies. This vision of the next millennium is not a particularly comforting one, regardless of how logical and insightful it might be, but it is a direct result of her intellectual coming-of-age. The Ginkgo is thus a very prophetic book. It's also complete fiction. An excerpt:

g how to realize its full potential; her former high school classmates represent society’s pre-occupation with a traditional culture that may not be exactly what it seems. We participate main character's life by reading what she’s written about her past experiences, her thoughts, feelings, desires, and observations. We participate in the traditional culture through a variety of literary devices, but primarily that of a teacher who recognizes this student’s creative potential and is determined to make it a powerful weapon for changing society. The main character chooses a ginkgo tree as her means of exploring her new environment (the university), and eventually envisions her traditional culture a thousand years hence, when her chosen ginkgo tree dies. This vision of the next millennium is not a particularly comforting one, regardless of how logical and insightful it might be, but it is a direct result of her intellectual coming-of-age. The Ginkgo is thus a very prophetic book. It's also complete fiction. An excerpt:

Thus I picked the ginkgo because it lets me imagine myself in a horror movie, with dinosaurs rampaging around on all sides, and discovering a ginkgo tree, then saying “gee, that’s the tree I picked for biology! How did it get inside this horror movie?” If the ginkgo could talk, it would probably be asking the same thing about me. Would the ginkgo think that the world I live in today is a horror movie? I don’t know. But sometimes it looks that way, doesn’t it? I have this disturbing feeling that maybe ginkgos remember the age of dinosaurs as wonderful, free, young and exciting times, and now consider the age of humans a terrifying, crazy, out of control time.

The Ginkgo is available as a paperback on Amazon.com, as an e-book on Kindle and on all other e-readers via Draft2Digital.

PIECES OF THE PLAINS: MEMORIES AND PREDICTIONS FROM THE HEART OF AMERICA

Pieces of the Plains, (J&L Lee, Lincoln, NE, 2009) subtitled Memories and Predictions from the Heart of America, addresses the questions: Why do people decide to study nature? What do we learn from nature? How does our understanding of nature develop? And finally, what does a scientist's lifetime of interaction with our planet, and especially with the multitude of organisms that share Earth with us, tell us about our future? The setting is America 's heartland, our literal geographic center: the prairie landscape from Oklahoma to Nebraska. Characters range from a dying grandmother, to a father passing a beloved childhood toy to his son, to world-renowned scientists, to a horse in the Sandhills. As readers, we contemplate life from an intensive care unit, play the role of professional photographer, look through a microscope to see the world in a unique way, join a rogue prospector looking for uranium in unlikely places, participate in a branding, and step into the rarified atmosphere of Ivory Tower politics. In the end, this experience leads us to ask: What is a human being? and What will human life be like in two thousand years?

Indeed, these questions are the last two chapters, the “predictions” of the book's title. Pieces of the Plains can be considered a scientist's memoir because it draws on a lifetime's worth of my teaching, research, and writing, but throughout the book I try to step back from the personal history in order to place these experiences into a global context. Original drawings accompany each chapter. An excerpt:

Nothing, it seems, can live in this part of North America without showing evidence of having encountered Permian surface geology—soils laden with iron and derived from a period in Earth's history when oxygen levels were high. My grandfather's car was always dirty; red clay was always packed up under the wheel wells, splattered there along some muddy red road where he drove, like every wildcatter of the early oil boom days, walking around with his geologist's pick, convinced there lay a financial windfall of indescribable size and importance just beneath the next hill.

The windfall never comes. Instead, we have photographs. A group of men stands on a cut bank beneath a tarp rigged as a tent. To the far right is my grandfather. He's smiling, squinting at the camera. We also have his notes on the back. “First commercial carnotite find at Cement Caddo Co. Found in School gymnasium yard. Sold to Lucius Pitkin Inc. Grants N. Mex. 13 tons ore, averaging 2.66 assay brought $3417.00 and a $2400 bonus by the Atomic Energy commission. Stringer, was 70ft long—averaged less than 3 ft wide and two feet thick. Had the deposit covered an acre, would have brought over $400,000.00. Lister Brothers of Chickasha finders.” At the time—middle 1950s—$400,000 would indeed have been a small fortune for these men. Whatever geological vagaries had conspired to deliver this $6000 “ 70 ft ” shallow stringer of carnotite to a schoolyard in southwestern Oklahoma had also conspired to tease this group of explorers with the same mineral bait that had snagged oil boomers a generation earlier and land boomers a generation before that. All six men in the Caddo County photograph could not have been full time prospectors. Five of them are young enough to need a day job. Only my grandfather looks carefree, standing there in a plaid shirt with his hand on his hip, a man beside a stringer.

Pieces of the Plains also is available on Kindle and all other e-readers via Draft2Digital

CONVERSATIONS BETWEEN GOD AND SATAN

CONVERSATIONS . . . SATAN, subtitled Held During October, 2004, at the Crescent Moon Coffee House in Lincoln, Nebraska, USA, Earth, Milky Way, is science fiction. The book is a biologist's response to military conflict arising from religious beliefs, exactly the kind of thing you read about in the daily newspaper and hear about daily on radio and television. CONVERSATIONS starts from first principles: both God and Satan are eternal, and God is all-knowing and all powerful, i.e., able to do anything, be anything, and go anywhere at a whim. The following exerpt has been included in Low Down and Coming On, an anthology of poetry about pigs published in 2010 by Red Dragonfly Press. An excerpt:

a biologist's response to military conflict arising from religious beliefs, exactly the kind of thing you read about in the daily newspaper and hear about daily on radio and television. CONVERSATIONS starts from first principles: both God and Satan are eternal, and God is all-knowing and all powerful, i.e., able to do anything, be anything, and go anywhere at a whim. The following exerpt has been included in Low Down and Coming On, an anthology of poetry about pigs published in 2010 by Red Dragonfly Press. An excerpt:

God was beginning to think that maybe people were not such a good idea after all because the planets that still had only dinosaurs and trilobites and giant dragonflies seemed to be doing just fine, so that maybe when He got tired of watching velociraptor types chomping down on gentle herbivores, instead of killing them off with a big meteorite, He'd just see if He could evolve them into pigs of various sizes and shapes. “I like pigs,” He said to Himself, and thought about the pleasure He felt when He was watching strange plants and animals evolve from other strange plants and animals, sort of like He'd created a circus over whose acts He had no control whatsoever.

“Birds,” said Satan, reading God's mind and reminding Him of His own operating principles. “You can't make pigs out of velociraptors. You can only make birds.”

“I forgot,” said God; “pigs are made out of something else.” God loved pigs because they were so honest and successful and, well, predictable. They simply acted like pigs, and even the various wild species He'd watched evolve out of some even-toed ancestor non-pig. All the pigs that had evolved out of their even-toed ancestors on millions of other planets also were great pigs and would probably have done just fine on Earth, even though they came in a variety of styles, sizes, and colors, including purple or iridescent chartreuse, depending on the galaxy. “You gotta admit it,” said God; “pigs are one of my Universe's best products.”

“It is amazing, isn't it,” replied Satan; “that people act like pigs but pigs never act like people.”

CONVERSATIONS is available as a paperback from Amazon.com, as an e-book on Kindle and on all other e-readers via Draft2Digital

TUSKERS

TUSKERS is science fiction. Aside from backstory, all the action takes place on the day of the OU vs. Nebraska football game, November 25, 2090; i.e., it's far into the future, OU has joined the Big Ten, and the Rose Bowl has been destroyed by an earthquake, so the national championship game again gets played in the Orange Bowl. However, to get to this game, Nebraska must beat OU. To complicate matters, Nebraska has not lost a football game in 10 years, but OU has developed some secret weapons. Thanks to the molecular biologists, the former Cornhuskers are now the TUSKERS, and their mascot is a wooly mammoth, yes, a real, live, mammoth resurrected from a frozen carcass, who could have no other name than Archie. In this scene, the Cornhuskers have yet to become the powerhouse TUSKERS, Nebraska is in the depths of a string of losing seasons, and Archie the wooly mammoth has been fixed up with a blind date who stands him up. Suzi, who will become one of the book's heroes, is still a college student. An excerpt:

So, one of the guys from the Beef Lab took Archie to the game. There were very few people around, and most of them were dressed in purple, not red. Even the Kansas State fans wouldn't travel to watch such a boring game. Archie didn't see anybody in red except the band and he knew that after his performance in the parade nobody in the band would go out with him. Finally two people wearing red showed up, but they were both male. Another person, the only female not dressed in purple or in the band, had on jeans and a brown leather vest. It was Suzi on her way to the museum and art gallery.

When Suzi saw Archie she stopped and stared. Even though Archie was six years old and seven feet tall, and Suzi had watched the mammoths from the public viewing area, she'd never been this close to one. By this time Archie was feeling pretty depressed, sad, and abandoned. Maybe Nancy doesn't like me because I'm big and hairy, he thought. If she only knew how intelligent and sensitive I am, she'd like me. The guy from the Beef Lab said “don't cry, Archie.” But Archie began to cry anyway, hanging his head, letting the tip of his trunk drag on the concrete, and blinking out tears that hit the sidewalk like water balloons.

Suzi was devastated. She could never have imagined the power that a crying mammoth could have over her deepest emotions. She walked up to Archie's handler and asked what was wrong. The man said “he was supposed to have a blind date but she stood him up because he's so big and hairy. Now he's all depressed.”

To which Suzi replied, “he's no worse than some of the football players.”

This wisecrack made Archie cry all the more, his massive body heaving with gigantic sobs and three feet of snot gurgling in his trunk. Suzi had insulted him terribly; he thought football players were barbarians. Then Suzi said “When I get depressed I usually kick the shit out of something. Usually something big. That makes me feel better.”

“Uh-oh,” said the guy from the Beef Lab. The only big thing around to kick was the Kansas State team bus, a superslick black-windowed silver coach with an abstract purple wildcat on the side.

Archie's ears perked up. Then he raised his head, wiped a tear with his trunk, blew out three or four gallons of snot, reared up on his hind legs and smashed the KSU bus. Metal and glass went everywhere. The two guys in red shirts stood off to the side. One of them said

“Wow! Tusker power!”

The other said “that's cute; Tusker power.”

The first guy yelled “ Tus-ker! ”

The second guy yelled “ Pow-er! ”

The two students looked at one another. Something out of their distant past, maybe something acquired by their grandparents, bubbled to the surface, as they began to chant: Tus-ker! Pow-er! Tus-ker! Pow-er!

TUSKERS is available as a nice paperback from Amazon.com, as an e-book on Kindle and on all other e-readers via Draft2Digital

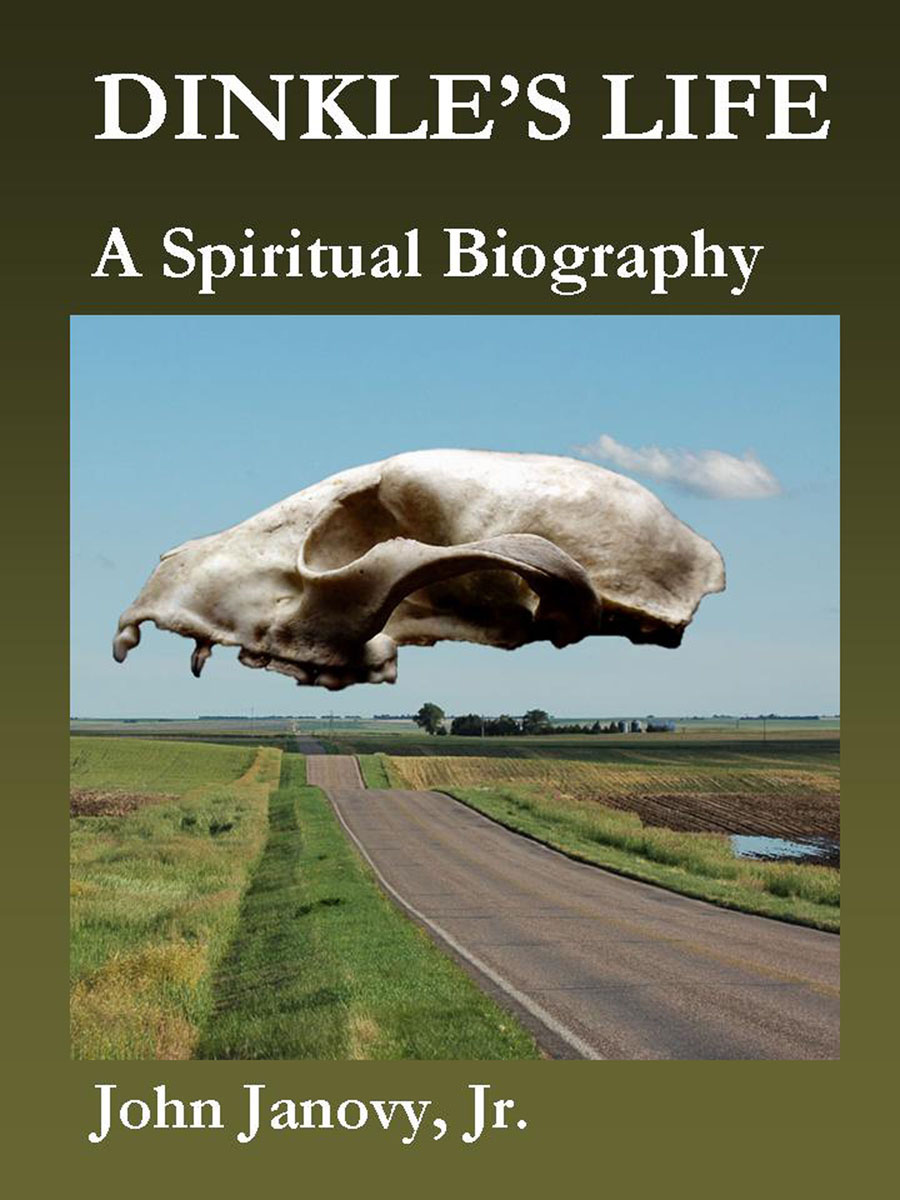

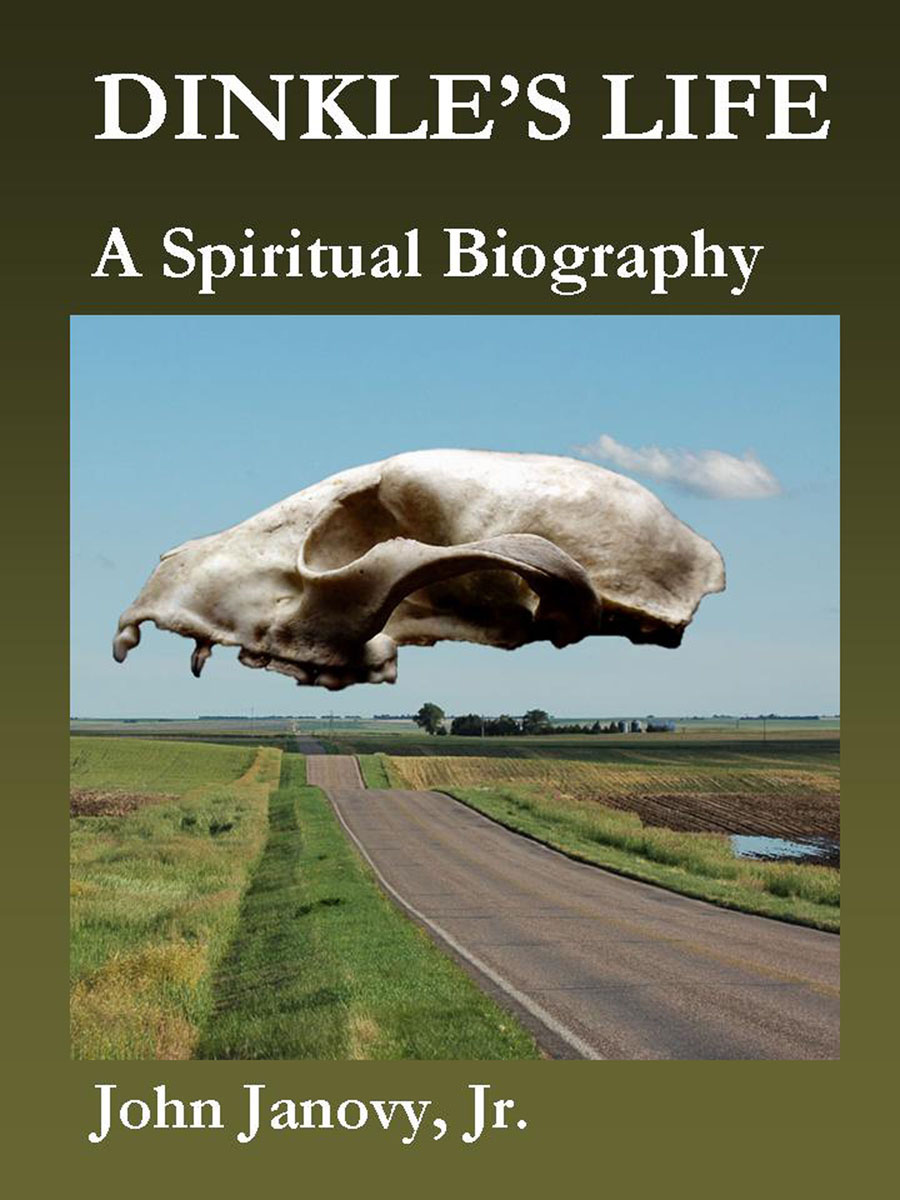

DINKLE'S LIFE: A SPIRITUAL BIOGRAPHY

DINKLE'S LIFE: A SPIRITUAL BIOGRAPHY, is the ultimate ghost story. He’s now a famous philosopher and mathematician, but as a teenager, Dinkle digs up an ancient burial mound, releasing spirits that now plague modern civilization, especially the West. These spirits are the God of Growth, the God of Fiction, and the God of the Group. The God of Fiction produces the lies of men in power; the God of Growth stimulates us to increase our use, exponentially, of limited resources; and, the God of the Group drives us to hate “the other” with a passion that leads so often to violence. Dinkle's trek through the Plains to find those spirits, kill them, and return them to their graves, is an epic adventure closely tied to the American Dream. DINKLE’S LIFE is a ghost story, yes, but one with profound meaning for the modern world. He has help, not all of it welcome! An excerpt:

Like an amoeba; just like a goddamn running, yelling, but worst of all, touching, amoeba, she thinks, as she watches children flow out of the long yellow bus. The amoeba moves up the marble steps toward her, a multi-colored mass of smelly little bodies herded by a heavy-set teacher in run-down shoes. The sweaty brats will stink; the teacher will be exhausted from a long climb in the unseasonably hot last week of school. Why did I volunteer to work at the museum, she wonders; why did I ever agree to give tours? Because that’s what women in my situation do, she answers herself. They don’t work as clerks in dry good stores; instead, they serve as docents in local museums. They give of themselves because their husbands can buy anything they want.

Out in the parking lot her new white Mercedes gleams in the hot sun. Her high-heeled lizard shoes match perfectly a stylish belt and complementary earrings. She has her script memorized. Thank God there are no American Indians or blacks in this group. She never felt she was able to say anything meaningful to black kids, and the Indians embarrassed her. She feels most comfortable playing like an expert on arrowheads and flint scrapers when the group is all white, and especially if the girls are nicely dressed. Nor does she mind the Hispanics; they are mostly Catholic, and consequently quiet and well-behaved, although still not very receptive to her spiel.

Inside the building, the teacher smiles, wipes her forehead, and pushes the children into a group, speaking harshly to a few, and finally gets them all facing the docent. Around each neck is a yarn loop holding a name card. Good; she could ask questions by name: Michelle, now why do you suppose these people painted their stories instead of writing them? A dozen hands go up. They didn’t care what Michelle supposes; they just want to tell their version of some experience that pops into, or out of, their minds. I painted a story once! My brother painted a story once! Hey, lady, one time we were out at my grandpa’s farm and we found a arrowhead (“err’haid”)!

Michelle? Michelle is shy, sucks on her finger. I know, ‘cause they didn’t know how to write! A freckly-faced redhead blurts out Michelle’s answer. His friends laugh. You cain’t write neither! Douglas, be quiet! says the teacher. Michelle, can you answer the lady?

I don’t think the Indians knew how to write back then, says Michelle softly. That’s right, Michelle; written language had not been invented, so they kept records with pictures and stories.

Good! What else hadn’t been invented, Michelle

Atomic bombs, answers Michelle, and television sets, and cars, and cell phones, and assault rifles, and telescopes, and computers, and electricity, and improvised explosive devices, and . . . and . . . and.

That’s enough, Michelle, says the teacher; that’s enough.

But I think they made pretty pictures on their teepees anyway, continues Michelle, ignoring the teacher, and they probably had good ideas.

And they used them hatchets to bash in each other’s skulls! says Douglas. His friends laugh. Yeah, Douglas! And they’d shoot you in the ass with one o’ them arrows (“errs”)!

The docent is ready to shoot Douglas in the ass with an arrow herself. If she’d been able to get into the glass cases she’d probably have done it. She looks at her watch. Need to hustle these kids on. Supposed to meet a friend for lunch before her tennis lesson. The group moves on, but Michelle stays behind, staring into the case.

Why did one of them paint a picture of a raccoon? she asks. Nobody is around to answer. Her teacher calls; come, Michelle, we need to move on. But Michelle does not move on. Something about that raccoon behind the glass keeps her attention fixed. I wonder, thinks Michelle to herself, why a raccoon was important enough to paint its picture. The question sticks in her mind. When she gets home that night, she gets on the Internet to learn as much as she can about raccoons.

DINKLE'S LIFE also is available on all e-readers via Draft2Digital.

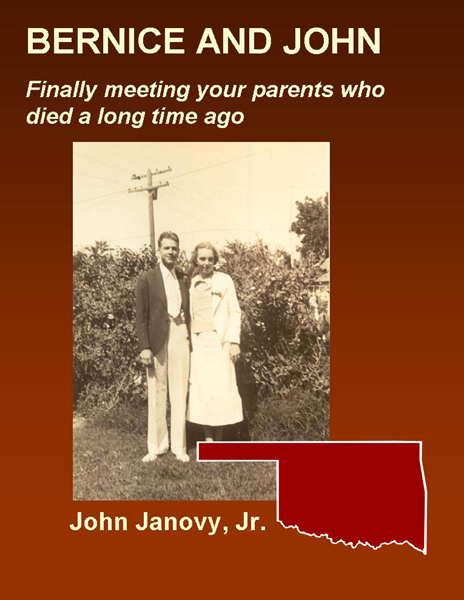

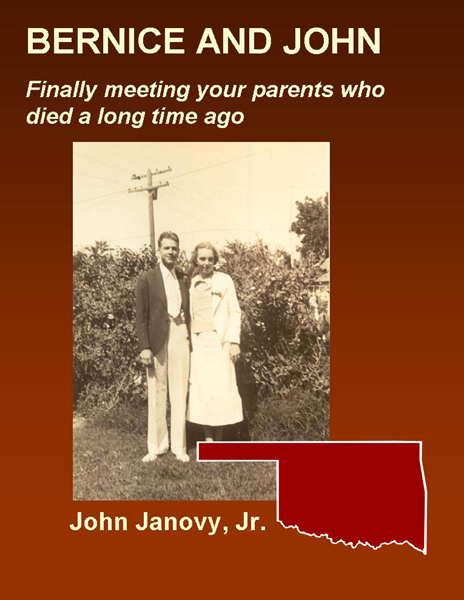

BERNICE AND JOHN: FINALLY MEETING YOUR PARENTS WHO DIED A LONG TIME AGO

Bernice and John is the story of my parents, both of whom died young, as best I can reconstruct that story from the photographs, letters, and memories they left behind. This book is also post-war Oklahoma history, of a sort, mainly because that's where these two young people met, dealt with the personal impact of global events, and managed to rear my sister and me to adulthood. The Oklahoma historian Angie Debo claimed “. . . all the experiences that went into the making of the nation have been speeded up. Here all the American traits have been intensified.” This is the Oklahoma that my parents lived with, the territory that my father explored daily looking for oil. And this is the richly diverse and challenging place that I encountered as a budding young scientist so unknowingly well equipped as a result of Bernice and John’s handling of me as a child. An excerpt:

I might have asked why it was so necessary that my sister and I play the piano, and why did it have to be a Kurtzmann baby grand dominating our living room instead of a run-of-the-mill spinet like those tucked away in the corners of my friends’ houses? Why did we own that album of Dvorak’s Slavonic Dances, a dozen 78 rpms in a rather elegant book with pockets for leaves? Why did our dining room furniture have to be hand made by a single person, like the house in which I was born? Where did she pick up the talent for judging my father’s business associates so quickly and why was she right on target 100% of the time. How did she and my father acquire these upper class trappings on a decidedly lower class salary? And why did she keep a loaded shotgun beside her bed when he was away? There is only one of these kinds of questions that I can even begin to answer with certainty from having been acquainted with this woman for only 24 years: why, as a terminal cancer patient, did she decide to go to college?

BERNICE AND JOHN is available as an e-book from Draft2Digital and Amazon.

INTELLIGENT DESIGNER: EVOLUTION FOR POLITICIANS

INTELLIGENT DESIGNER: EVOLUTION FOR POLITICIANS, is my [admittedly naïve] attempt to introduce some scientific literacy into the the American population. An excerpt:

Politically active creationists have managed to keep the word “evolution” in the center of the debate over human origins, which to be honest is an entirely political one, that is, a culture war, but one with very real consequences for our nation. Scientists have established, unequivocally, that humans evolved from non-human primate ancestors. We may not know exactly which one of these ancestral species was our progenitor, but based on the scientific evidence, it is abundantly clear that there are several good candidates among the now-extinct primates that inhabited Africa five to ten million years ago. Those discoveries have not done much to erode the belief, among conservative Christians and those who scientifically illiterate, that we the people are not “descended from monkeys” but instead made by God in God’s image.

Belief may trump knowledge in the political arena, but never in the arena of life on Earth. We will, eventually, live out our species’ destiny as really smart apes, whether that destiny be obliteration by nuclear weapons of mass destruction, starvation and genetic bottleneck once our population reaches its so-called stable limits, or destruction of the biosphere to the point that our populations are no longer sustainable. The time when we get our biological come-uppance cannot be predicted accurately, but it can certainly be estimated, based on per-capita water use and the global petroleum supply. Most scientists estimate that time somewhere near the end of the current century, that is, 2060-2100.

INTELLIGENT DESIGNER is currently available as a free pdf download at www.johnjanovy.com/IntellDesign.pdf. Feel free to send copies to all your friends and elected representatives.

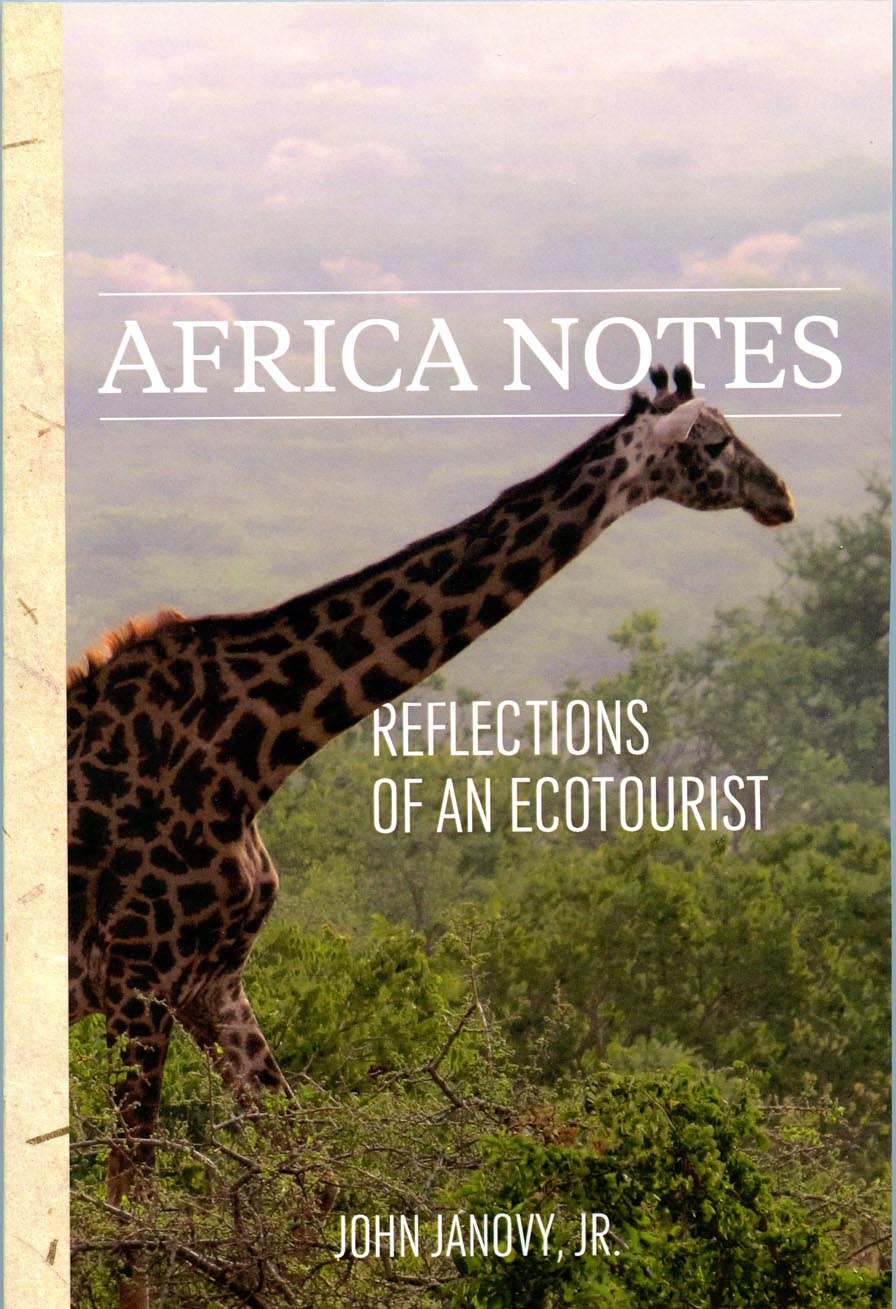

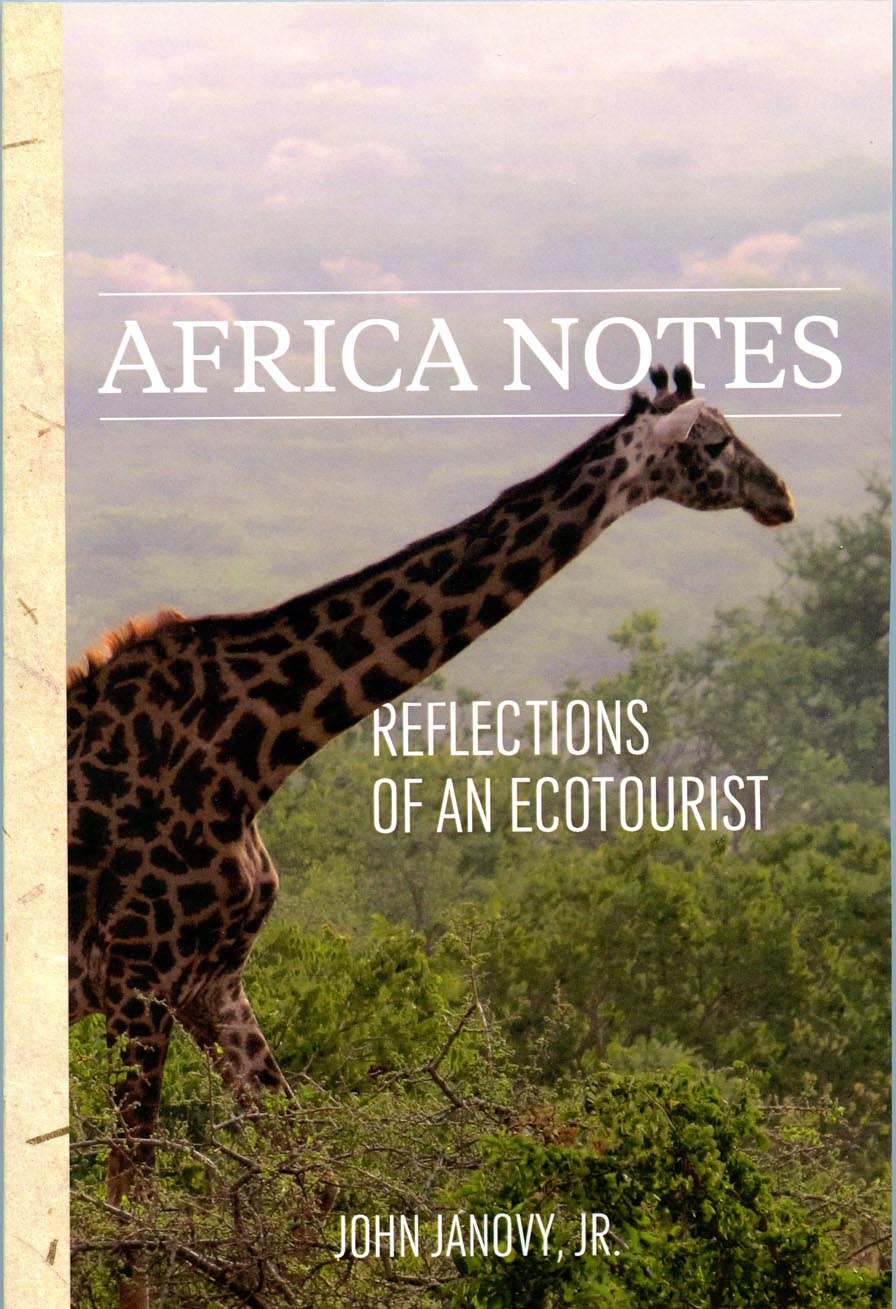

AFRICA NOTES: REFLECTIONS OF AN ECOTOURIST

AFRICA NOTES: REFLECTIONS OF AN ECOTOURIST, is a "report" from two life-changing trips to Africa, one to Botswana and one to Tanzania, with a group from the Lincoln Childrens' Zoo. An excerpt:

As I sit in Prosper’s Land Cruiser taking photograph after photograph and video after video, of the most cooperative and non-self-conscious ostriches, usually in groups, males and females in equal numbers, two experiences from the past decades come back, both of them involving cultured birds, and both in Oklahoma. The first was a conversation with a parasitologist friend, Al Kocan, now deceased, but then on the faculty of Oklahoma State University where he was developing an ostrich herd (flock?) for commercial purposes. At one point he commented that none of the artificial diets they’d tried were very successful in helping chicks survive their first few months of life. They do best, he remarked, when we just let them out in the pasture to fend for themselves. All that pecking must produce some combination of nutrients that humans don’t know about, probably including dirt.

The second encounter occurred when Al took me into the hatchery. Looking into a large stainless steel and glass rearing incubator, he noted that one egg had just hatched and the chick was lying there. I asked to hold it. He reached in, took out the newly-hatched bird, not even an hour old, and placed it in my hands. At that point, I knew I was holding a dinosaur. It’s an experience I have never forgotten, a link, through touch, directly with the Cretaceous. In later years as the biological evidence accumulated for an evolutionary history in which modern birds, all nine thousand species, are indeed considered dinosaurs, my experience that day with the ostrich chick has surfaced over and over again in my thoughts. Those five minutes are among my most treasured memories from a professional career as a biologist. In the Ngorongoro Crater, I put my camera down and just watch ostriches peck at the ground. When one of them finally stops and looks up at me, it’s with a teacher’s eye. “John,” it’s saying, “welcome to the past.”

AFRICA NOTES was published by the University of Nebraska Center for Great Plains Studies. It's available as an e-book from Draft2Digital or Kindle and as a paperback from UNL Maps and More .

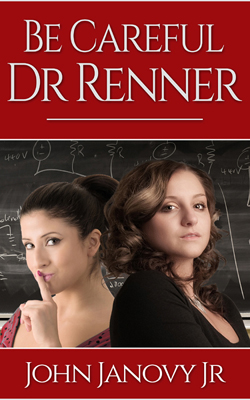

BE CAREFUL, DR. RENNER

BE CAREFUL, DR. RENNER, is the first installment of the Gideon Marshall Mystery Series, a five-book exploration of scientific illiteracy in high places, arrogance derived from extreme wealth and power, and the potential lethality of some obscure scientist's theoretical research. Oh, and there is also revenge (a perfect murder!) by a couple of bullied staff members at a small Iowa college. An excerpt:

I smiled a funeral home director’s smile. At the time I thought: we are not going to hear from any of Clyde’s surviving relatives. He was not exactly the kind of man you’d envision having relatives, or caring about them if he did. The mementos were mainly igneous rocks, meteorite fragments, shards of obsidian, graphic granite, and award plaques, all souvenirs from Clyde’s numerous travels around the world, and all displayed in a way that reminded you of his importance, manifested in his invitations to speak at various conferences. At the time of Branch’s visit, it never occurred to me to ask him how many times before some representative from Campus Security had actually visited departmental offices after a faculty member died. I suspect that number is zero. Geology was very likely the first, and only, such visit, and Renner was obviously the reason.

Why is an apparent heart attack, alone at night after walking home from school, such a mystery? Again, if you’ve watched much TV, you know the answer: because there was a palpable sigh of relief when we got the announcement. If we had been in a faculty meeting when the news broke, there could easily have been applause. Thus we have the wondrous transformation of campus policeman Leonard Branch into sleuth, also known as pain in the ass to those of us now on his persons of interest list.

Nothing in my education, no experiences in my background, prepared me for a place of honor on such a list.

BE CAREFUL, DR. RENNER s available as an e-book from Draft2Digital or paperback from Amazon.

THE STITCHER FILE

THE STITCHER FILE, is the second book of the Gideon Marshall Mystery Series, a five-book exploration of scientific illiteracy in high places, arrogance derived from extreme wealth and power, and the potential lethality of some obscure scientist's theoretical research. The obscure scientist is Dr. Rebecca Stitcher, a reclusive genius, murder victim, and [former!] faculty member at Cavanaugh College, an off-the-scale wealthy and exclusive college in southern Iowa. A couple of excerpts:

First excerpt:

Dr. Chatterjee looks out her office window at the sleet and snow moving sideways, blanking out the familiar scene that tells her she’s at work: industrial buildings, a warehouse, and run-down frame houses. She needs to go home before she’s locked in by the blizzard. She looks at her watch; 10:23 AM. She will never forget the time when her smart phone played its familiar tune, or the number that now displayed on the small screen in her hand.

Second excerpt:

It’s not difficult to picture the scene: Elizabeth Bennett gives her husband Joe a peck, walks out the back door of their farmstead, warms up her car while scraping the wind-shield, drives out the long gravel tracks between leafless apple trees, and turns out onto Route 3. A mile down the road, where Union Pacific tracks cross, she sees something in the middle of the road, something that looks like a deer that’s been hit by a vehicle, one of the nearly fifteen thousand whitetails killed on Iowa’s roads every year. She puts her car into park, gets out, leaving the door open, and bending her head against the wind and sleet, stomps up to the animal. A few feet away she figures out that this is no deer carcass. She takes a closer look; it’s a small female body; her heart rate soars; she looks to the face, wondering who it might be.

“What about her face, Elizabeth?”

“It’s gone, Dr. Marshall! Her head is half gone!”

THE STITCHER FILE is available as an e-book from Draft2Digital or Amazon.

THE EARTHQUAKE LADY

THE EARTHQUAKE LADY is the third installment of the Gideon Marshall Mystery Series. Here are two excerpts:

First excerpt:

“There were other empty prescription bottles in her house,” says Chatterjee; “as well as in her office. Not only was she taking Ambien that she got from someone, she was taking Inderal for high blood pressure. She had a script for the Inderal.” The medical examiner looks at a page and shakes her head. “Cafergot; a combination of caffeine and an ergotamine. Dr. Stitcher also had migraines, and she was also taking a slew of over-the-counters.”

“A ‘slew’?”

“Well, not an unusually large number, compared to some of the cases we get, but enough: low-dose aspirin, regular aspirin, Tylenol, Aleve, psyllium husks, stool softener, a bunch of vitamins, most of them at way over recommended daily doses, naproxen, iron supplements.” Her fingers trace down the list that starts on page thirty and ex-tends for another page. “A lot of it came by mail order. Here’s an interesting one, given the others on the list: No Doz Max.” She shakes her head. “Can’t sleep, gets somebody to give her Ambien, then can’t wake up, so loads up on caffeine.”

“This woman was psychotic,” says Burkholder. Chatterjee flashes him one of her very rare irritated looks.

“So far,” I respond; “you’ve told me more about Rebecca Stitcher in the past fifteen minutes than anyone in our department has learned in the last fifteen years."

Second excerpt:

“We have a very large file on everyone associated with the victim in any way,” Burkholder answers; “including you and all the members of this department. You testified in a murder trial in Oklahoma.” He pauses. “I’m sure you remember the soil samples?”

Of course I remember those samples, my days at the microscope, and my conclusions about the origins of dirt in the victim’s clothing.

“So that makes me an expert witness in the Stitcher case?”

“We have some plastic bags that we’re going to leave with you, Dr. Marshall.” Aparajita Chatterjee is once again totally professional—no smiles, no warm hand, no silver bracelets sliding down her arm, and no sparkle from those darkest of eyes, only the look of a tired pathologist ready to be home. “But first we need to finish with the report, so you’ll understand why we’re here.”

And with that declaration, she reaches across my desk and flips the pages of my autopsy report copy over to the opening photographs. Once again, I’m looking at the shattered bones, what’s left of her mouth, her bare teeth, and the skin torn away from her cheek and lower jaw. From the other side of the picture her remaining eye, strained open, glares at me, that familiar look from Dr. Rebecca Stitcher, even in death. She’s sleeping, forever, and this time without the help of a date rape drug supplied by an unknown person, under unknown circumstances, in a community that seems to know everything about everyone.

THE EARTHQUAKE LADY Is available as an e-book from Draft2Digital or either paperback or e-book from Amazon.

THE WEATHERFORD TRIAL

THE WEATHERFORD TRIAL is the fourth installment of the Gideon Marshall Mystery Series. Dr. Charles Weatherford, an important character in the first three Gideon Marshall Mysteries, has been arrested for the murder of his departmental colleague, Dr. Rebecca Stitcher. Here are two excerpts:

First excerpt:

Outside the rain patters on her window. The face on her ceiling light is now that man from the college, that geologist. She aims for his eye and pulls the trigger again. Next, the face is that of his wife, that woman with a pistol who slammed into her house last week, barging through the screen door as Naomi answered the bell and put her on the floor, aiming that handgun at her forehead before Naomi could get her own weapon then asking those questions to which she had to answer “no”—Is it loaded? Have you ever fired a gun? The rain comes down a little bit harder. The faces on her ceiling light go away then return, over and over again, always in the same order. Naomi drops the pistol onto her bed covers and cries herself to sleep.

An hour later she sits up in bed, swings her feet over the edge, and looks at her image in the dresser mirror. She stands up, pulls a robe off the end of her bed, slips it on, and walks barefoot into the kitchen. There’s a box of dry cereal on the kitchen table, just where she left it the day before. She reaches into the cupboard, gets a bowl, pours cereal, sits down, picks up the spoon she used yesterday and left on the table, and starts to eat. Thirty minutes later she walks back into her bedroom, finds the black sweats where she’d dropped them on the floor by her closet, dresses, and retrieves her shoes from under the bed. She picks up her pistol. Her long coat is hanging on a hook behind the front door. It’s still raining, but not quite as hard as earlier. She walks out the front door without locking it, walks up her driveway and turns left. An hour later, she’s at Highlands Cemetery.

Second excerpt:

“Good morning, Dr. Marshall,” she says; “I’m Officer Reid. You may remember that I delivered some material to you a few days ago?”

“I remember.”

“This is Krystal Krueger, your new staff member.”

“We don’t have a new staff member.”

“You do now.”

Krystal Krueger extends her hand. Her grip is firm, reminding him of Broderick Burkholder’s, the Bruce Willis clone from Department of Criminal Investigation who’d arrived, with Aparajita Chatterjee, the Polk County medical examiner, on that Friday before spring break to deliver the plastic bags and the autopsy report on Rebecca Stitcher.

“Nice to meet you, Dr. Marshall,” she says.

“We’ll be bringing in an additional desk and chair sometime later today,” says Officer Reid. “There’ll probably be some paperwork and family pics to go on the desk, make it look used. The men will help you rearrange the furniture.”

“Rearrange the furniture? Krystal will have a new desk?”

“It will probably be one from your campus inventory,” answers Reid; “make it look like she’s been here a while.”

“Everyone on campus knows we only have one desk in this office.” Marshall plays along, not wanting to believe what he’s beginning to suspect, a suspicion confirmed by Krystal Krueger herself.

“It’s reasonably important to us that we keep track of potential witnesses,” she says.

“You’re protection for Marshall?” Branch asks. Marshall forcibly suppresses a smile at Branch’s tone of voice. “Marshall needs protection?” He looks her up and down. “And you’re gonna protect Marshall?”

“No problem. And you are?”

“I’m Leonard Branch,” he answers; “senior detective from campus security.”

“Nice to meet you, detective Branch,” says Krystal; “I believe we’ll be just fine.” She’s struggling to keep a completely neutral expression. Marshall can tell that the name “Columbo” is racing through her mind.

“Okay,” admits Marshall; “what do I call you? Ms. Krueger? Or Krystal?”

“Address me the same as you would the rest of your staff.”

“Would you like some real duties?”

“Maybe.”

“Anything else I need to worry about?”

“No,” replies Krystal Krueger; “although we do need to talk in private, so if we could excuse detective Branch, that would be appropriate.”

“You armed?” asks Branch.

“Yes,” answers Krueger.

“We’re a weapons free campus,” says Branch.

“Not anymore.” She nods to Officer Reid, who takes Branch by the arm, gently and leads him out, closing the door behind him.

“So tell me, Krystal,” says Marshall; “do we really need an armed guard?”

“You’re an expert witness,” she answers; “we intend for you to show up.”

THE WEATHERFORD TRIAL Is available as an e-book from Draft2Digital or either paperback or e-book from Amazon.

DELMAR'S OIL

DELMAR'S OIL is the fifth installment of the Gideon Marshall Mystery Series. Delmar Stevens, psychotic, multi-billionaire, oil magnate with dreams of owning a machine for making earthquakes and volcanoes happen on purpose at selected locations, puts his plans to a test. Here are two excerpts:

First excerpt (Library director Madeleine Boecker and Gideon Marshall start down into the archives):

Madeleine Boecker gets up and greets him with a handshake.

"Coffee?”

“No thanks; I’m okay."

“Ready for a walk downstairs?”

“Down in the darkness, wherein lies all the lies, disappointments, forgotten and rejected manuscripts, bad ideas, great ideas now lost, or hiding in an unlabeled file, embarrassing poems, nasty letters, and above all, boxes and boxes of pure crap generated by the intellectual elite.”

“That’s one way to put it,” she says; “but eventually someone will want to uncover what happened when, where, and why, and who was involved.”

“Playing detective.”

“That’s exactly what we’re doing, Dr. Marshall,” says Madeleine Boecker; “playing detective.”

“On a cold case, in which the prime suspect has just been acquitted.”

Second excerpt (Geologist Jed Knapp finishes his review of Hansmeyer #1 with Delmar Stevens):

Sixteen minutes after being handed the electric log, Jed Knapp is ushered out the side door, which closes behind him. Standing for a moment in the semi-darkness, he hears a dead bolt. In what seems like a spatial eternity, there in the distance is the exit door, toward which he starts walking. The scrubber hallway walls are covered with art—enormous framed photographs of Stevens Oil offshore platforms, dramatic action of crew members on a rig floor, magnificent sunsets with a massive derrick in the left foreground, hydraulic fracturing machinery with angles and shadows composed almost as if they were of some female nude, and greasy but smiling, multi-ethnic, roughnecks sitting around a table. He walks slowly through the scrubber, studying each piece of art, trying to memorize it, trying to erase the previous twenty minutes of his professional life. He pushes on the door at the end. It opens then snaps locked behind him. He’s in full fluorescent light. He finds the first men’s room. The movement sensor light comes on. He’s alone. Jed Knapp opens a stall door, drops to his knees, wraps his arms around the cold porcelain, and vomits up every meal he can remember eating in his life.

DELMAR’S OIL Is available as an e-book on Kindle, or Draft2Digital or paperback from Amazon.

DADDY'S GIRL: AN OIL BUSINESS STORY

DADDY'S GIRL is the sixth installment of the Gideon Marshall Mystery Series, although Marshall himself does not appear in this one. In this book, Delmar Stevens, billionaire owner/CEO, his top lawyer, and genius consultant are all arrested on conspiracy charges and Stevens’ 23-year old daughter Annabelle takes over the company.. Here are two excerpts:

First excerpt, Annabelle's conversation with a company attorney after the arrest of her father, the billionaire:

“And just how was this magnificent feat to be accomplished?”

“The earthquake machine? They’d evidently not only acquired the instructions for building such a weapon from drill pipe and fracking equipment, a set of design requirements and equations about how to make it work, all from research done by that prof up in Iowa, the one that got her head blown off for coming up with this mess, but they’d also tested the theory with some wells in southwestern Oklahoma.”

“And did the test work?" She gives him what she believes is the CEO stare.

“I have no idea, and neither do you,” he answers. “Doesn’t really matter if it worked; it only matters if they got together to try to make it work.”

Second excerpt, Annabelle trying to use her geology major to find out about a fake well used to test the earthquake machine theory:

“When my father hires women, they work in this building anywhere but legal.” She stands up and smooths her skirt. “And Connie, while you’re at it, get me the public records on this well.” She hands him the completion report on Hansmeyer #1. “Have Julie make you a copy. Maybe I can use that college education after all.”

“Want to talk about bail on those three?”

“I just want to see the person who spent time out on that rig. I’ll figure out what to do about the others after that.”

“Hate to change the subject, but have you thought about additional security?”

“Other than that pistol-packin’ Amazon my father hired to keep track of me for the last seven years?”

“If you’re talking about Amber Buchanan, yes. The fact that you’re here means she did her job, and she’s still doing it.”

“Why do I need additional security?”

“You’re in Texas,” he answers, “you’re an attractive young woman, you suddenly have a hell of a lot of power, and a hell of a lot of money at your fingertips, and whatever you end up doing with that power and money will make somebody mad as hell.”

“So, I’ll end up getting some hate mail, right? Some bubbas thinking a girl needs to be clinging to cowboys and doin’ them stupid line dances in a bar instead of buying leases, or some real Texas oll bidniss good ole boys hoping they can put their pipes down her hole, right?”

DADDY'S GIRL Is available as an e-book and audiobook on Kindle, or Draft2Digital.

GIDEON MARSHALL MYSTERY SERIES - BOXED SET

The Gideon Marshall Mystery Series boxed set is a combination of all the five Gideon Marshall books published so far. It's only in e-book form, but it's probably the bargain in tablet reading! Here is an excerpt from the last book in the series: Delmar's Oil. The boxed set is available at Draft2Digital.

“Mr. Stevens expects it to happen on schedule. Weatherford’s also free because of you. He owes you.” Norden Jamaison’s voice over the phone has that ‘do I need to remind you’ tone and Connecticut Bergen can envision the look on his face. Although Connie Bergan was a very wealthy man because of his own connections to Stevens Oil and the frequent opportunities to defend the company against various claims or settle them for what seemed like enormous sums to the recipients but were hardly noticed by Stevens himself, he’d never set foot in a criminal case courtroom prior to being assigned to defend Charlie Weatherford against a charge of murdering his department colleague, Rebecca Stitcher. His success in that venture—Weatherford’s acquittal—was due in no small part to the contributions of Amber Buchanan, and they both knew it. Bergen’s next call is to Amber.

“I need to get a message to Charles Weatherford and Annabelle is probably the only person who can deliver it and produce the desired results.”

“Let me guess,” she says, her voice producing a slight smile, even though it’s filtered through whatever background noise and electronic system connects them; “Stevens wants someone else to disappear and Weatherford’s success with Stitcher means that he’s now the company hit man.”

“I have another theory about who might actually be the company hit man.”

“Oh? Really?” she says. He has no idea where she is or who she’s with but he can see her face clearly in his mind. It’s a totally different face than he was envisioning ten seconds earlier.

“We can discuss it in private.”

“Across a pillow, I presume.”

“Stevens wants Weatherford in Irving later this afternoon. Or at least on his way.” He changes the subject back to business at hand. “I have no idea where Annabelle is, but I have this feeling that she’s the only one who can make him drop everything and get on a Gulfstream to Texas without even a toothbrush.”

“By ‘drop everything’ I assume you also mean his pants.”

“Amber,” says Connie Bergen the Stevens Oil attorney, “I received this command from Jamaison, and I probably need Annabelle’s help, which means I also need your help.” He pauses a few seconds before adding “actually, I think we all need to make this happen.”

“Assuming we all really want to keep working for Stevens Oil.”

“Yes.”

“And if that assumption is not correct?”

“Can we talk about it later?”

“Okay, but I believe she’s actually down in Texas already.”

“I’ll pick you up in ten minutes. We’re going to school.”

“I can hardly wait. Two hours of cows and corn, kidnap a dashing young professor, and another two hours of cows and corn so we can dump him on a plane to Texas.”

“There’s a lady on that plane who will make him a martini.”

“I know that lady,” Amber says; “she’s been known to make more than a martini.”

“From what I’ve seen of Charlie Weatherford, he’ll appreciate the martini and whatever else she has to serve.”

“Annabelle’s not around. She’s back at headquarters.”

Something in the tone of her voice tells Bergen that Amber Buchanan has just pulled up a screen on her smart phone and gotten a report of where Annabelle Stevens is at this very moment. A vision flashes through Bergan’s mind: Annabelle has just turned twelve and Delmar Stevens is having his daughter injected with a bar code strip that enables this tracking via satellite.

“And if he resists?”

“I’ll give him the option of coming with us or getting his head blown off.”

“Just like Rebecca Stitcher.”

“He should be familiar with the technique.”

“I’ll pick you up in ten minutes.”

LETTER TO A CHILD BORN TODAY

Letter to a Child Born Today is a product of conversations with various scientist friends over the past few years. In Letter to a Child Born Today, in despair over his nation sliding into authoritarian rule, an 82-year old scientist writes a 100-page letter to a new-born child whose name he’s just read in the paper. His nation is the United States; his letter is what life has taught him about what this child can expect if she lives to her birthday on March 21, 2100, during a global pandemic and our ongoing assault on the American Dream. Letter is available at Amazon and e-readers via Draft2Digital. An excerpt:

Here are some words that defined your world the day you were born: abortion, immigration, Trump, American, Republican, Democrat, climate, liberal, Nazi, terrorist, Black, White. Here is a word that defined your world a couple of years later, as I am trying to finish this hundred-page letter: COVID-19. Those are words used to define enemies and are readily attached to human beings; other of these words are linked to choices, behaviors, consequences of those choices, and beliefs that drive human behaviors. Some of those words may still be significant features of your environment when you are eighty-two.

If you are lucky, you will remember reading about these words in history classes, maybe even in college, and wondering how they could have been so important. If that happens, you can look in the mirror and say to yourself: Ashley, you are one exceedingly fortunate young woman—alive, healthy, smart enough and wealthy enough, or at least with enough available credit to float a loan, to end up in college, perhaps planning a career as a physician or attorney, during which my vocabulary will be expanded by several thousand new words, all of them with variable meanings, depending on who is using them and for what purpose they are being used.

I cannot begin to imagine the words that will define your world when you are my age, eighty-two, but I will try to do that later on, because without those words this letter cannot be finished. A whole lot of your words, at the age of eighty-two, will not be pleasant ones, and will not make you think of wonderful, happy, prosperous times, safe times. Why do I know this about the words that will surround you eighty-two years from now? I know about these words because they are the same words that have been used for at least the last thousand years, and probably for two or three times that long ago, although I’m referring to the meanings of sounds and symbols, not the sounds and symbols themselves. They are words with which I am familiar, with which my parents, grandparents, and great grandparents were also familiar. I promise that at the age of eighty-two, you are not going to like the sounds of those words, and they will be especially painful if you have loved ones—your parents, your children, your grandchildren—who have suffered, and maybe died because of them.

LIFE LESSONS FROM A PARASITE

Life Lessons from a Parasite is pulished by Sourcebooks (2024) and is subtitled What Tapeworms, Flukes, Lice, and Roundwormds Can Teach Us About Humanity's Most Difficult Problems and it uses parasites to show, for example, how some problems are beyond solution by our finest minds, how massively complex phenomena can be compressed into single words for use as political weapons, and how language can function as an infective agent. Life Lessons is available at amazon.. An excerpt:

Our fear of mosquitoes is derived from their role as transmitters of disease and the fact that they can deliver an itchy welt. My newly found love of mosquitoes was derived from knowing them for what they were; from seeing firsthand the differences in various species’ breeding biology and having to study their different wing veins and color patterns to identify them. Because of this work I became very well acquainted with organisms that most people kill without ever knowing or caring about them. Mosquitoes thus taught me that how, and why, you look at a stranger, along with whatever intellectual or cultural baggage you bring to the encounter, shapes your reaction to that stranger. Another life lesson from parasites, this time from ones that will suck your blood if you let them.

Of all those life lessons acquired from my research subjects, this one, relative to strangers and perceived danger, may be the most important. I know it has shaped my interactions with situations and people, including the thousands of students in my large classes over the years. Today my news sources are filled with examples of fear and rejection, mainly of the unknown and unfamiliar, exhibited by people in various positions of power, when caution and rationality are probably more appropriate responses. In these cases, the unknown and unfamiliar can range from scientific conclusions about climate change to the sexual orientation of neighbors, the impact of poverty on American citizens, and reproductive choices of women, just to name a few. Whatever intellectual and cultural baggage I brought to my encounters with Cheyenne Bottoms mosquitoes, that baggage was quickly abandoned when I entered their environment and studied them carefully and objectively, as legitimate inhabitants of my world. Yes, I saw nature’s incredible beauty instead of, or maybe in addition to, bloodsucking flies just trying to find their next meal.

My personal thanks to the approximately 15,000 individuals, mainly University of Nebraska students, fellow faculty members, and landowners who have contributed in various ways to the ideas and experiences in these books.

Return to Home Page

a biologist's response to military conflict arising from religious beliefs, exactly the kind of thing you read about in the daily newspaper and hear about daily on radio and television. CONVERSATIONS starts from first principles: both God and Satan are eternal, and God is all-knowing and all powerful, i.e., able to do anything, be anything, and go anywhere at a whim. The following exerpt has been included in Low Down and Coming On, an anthology of poetry about pigs published in 2010 by Red Dragonfly Press. An excerpt:

a biologist's response to military conflict arising from religious beliefs, exactly the kind of thing you read about in the daily newspaper and hear about daily on radio and television. CONVERSATIONS starts from first principles: both God and Satan are eternal, and God is all-knowing and all powerful, i.e., able to do anything, be anything, and go anywhere at a whim. The following exerpt has been included in Low Down and Coming On, an anthology of poetry about pigs published in 2010 by Red Dragonfly Press. An excerpt:

g how to realize its full potential; her former high school classmates represent society’s pre-occupation with a traditional culture that may not be exactly what it seems. We participate main character's life by reading what she’s written about her past experiences, her thoughts, feelings, desires, and observations. We participate in the traditional culture through a variety of literary devices, but primarily that of a teacher who recognizes this student’s creative potential and is determined to make it a powerful weapon for changing society. The main character chooses a ginkgo tree as her means of exploring her new environment (the university), and eventually envisions her traditional culture a thousand years hence, when her chosen ginkgo tree dies. This vision of the next millennium is not a particularly comforting one, regardless of how logical and insightful it might be, but it is a direct result of her intellectual coming-of-age. The Ginkgo is thus a very prophetic book. It's also complete fiction. An excerpt:

g how to realize its full potential; her former high school classmates represent society’s pre-occupation with a traditional culture that may not be exactly what it seems. We participate main character's life by reading what she’s written about her past experiences, her thoughts, feelings, desires, and observations. We participate in the traditional culture through a variety of literary devices, but primarily that of a teacher who recognizes this student’s creative potential and is determined to make it a powerful weapon for changing society. The main character chooses a ginkgo tree as her means of exploring her new environment (the university), and eventually envisions her traditional culture a thousand years hence, when her chosen ginkgo tree dies. This vision of the next millennium is not a particularly comforting one, regardless of how logical and insightful it might be, but it is a direct result of her intellectual coming-of-age. The Ginkgo is thus a very prophetic book. It's also complete fiction. An excerpt: